WHO releases guidance on using whole genome sequencing in foodborne disease surveillance

The World Health Organization (WHO) has released a comprehensive guide on the use of whole genome sequencing (WGS) as a tool to strengthen foodborne disease surveillance and response.

The guidance consists of three modules that provide detailed information on the implementation of WGS in the context of food safety.

The first module serves as an introduction and outlines the minimum capacity requirements for incorporating WGS into foodborne disease surveillance and response systems. This includes the necessary epidemiological and laboratory capabilities, as well as the capacity within the food safety system to effectively respond to outbreaks. The guide also offers options for integrating WGS into existing systems and targets public health professionals involved in foodborne diseases surveillance and response.

However, the guide acknowledges some challenges associated with WGS implementation. These include the lack of an internationally agreed standardized approach for WGS analysis, the need for training in genetic data analysis and interpretation among staff, and issues related to data sharing. The financial viability of WGS is also highlighted, emphasizing the importance of collecting an adequate number of isolates during outbreaks to make the technique cost-effective.

The second module focuses on how WGS can support foodborne disease outbreak investigations. It is intended for countries that are in the early stages of implementing lab-based surveillance for selected pathogens or have limited experience with WGS and wish to build capacity. The guide provides information on the advantages and disadvantages of developing in-house laboratory capacity versus outsourcing the wet lab component and bioinformatics analysis of sequence data. It also offers guidance on creating a business case for WGS and conducting pilot studies.

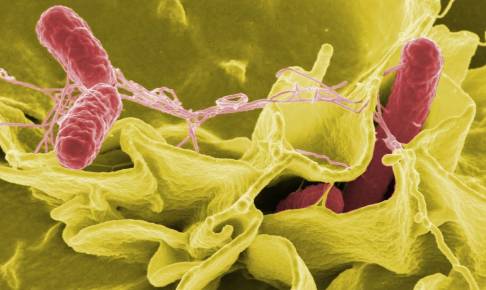

According to WHO, while WGS data does not provide definitive confirmation of the source of an outbreak, it does establish a more robust connection and aids in narrowing down the investigation's scope, ultimately enhancing epidemiological and traceback discoveries.

The third module is designed for countries that have already established lab-based surveillance of pathogens. It covers the use of WGS for monitoring trends over time, as well as its application in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and virulence factor monitoring. The guide recommends starting with a single pathogen for routine surveillance and scaling up as capacities in the laboratory and public health agencies are strengthened. It also addresses challenges related to defining clusters that require public health follow-up and provides guidance on sharing WGS results with public health agencies and reporting frequency.

The release of this guidance by WHO is expected to have a significant impact on foodborne disease surveillance and response worldwide. WGS has the potential to revolutionize the detection and monitoring of microbial hazards in the food chain, enhancing routine surveillance, outbreak detection, response, and source identification. By providing clear and practical recommendations, WHO aims to facilitate the adoption and implementation of WGS as a valuable tool in the fight against foodborne diseases.

The WHO's release of this guide underscores the organization's commitment to promoting food safety and reducing the burden of foodborne illnesses globally. With the appropriate adoption and utilization of WGS, countries can strengthen their surveillance and response systems, leading to more effective prevention and control of foodborne diseases.

Source: